Thinking — Fast and Slow

And now to something completely different…

Have you ever wondered why you make the choices in life you do — e.g. not learning from bad experiences?

Or why it is difficult for people to make good decisions about future — say, not saving up for retirement?

Or why people seem to make contradictory choices — e.g. valuing same things different in different contexts?

If so, then this book may be something for you…

Lying on my desk for almost a year, I finally found time to read it while traveling. And I loved it. Daniel Kahneman takes us through 30+ years of research that he and Amos Tversky have made since the 70s. It is a story about the two systems (the fast and the slow) in our brains, how they interact, and the mistakes they give rise to. It is engaging, surprising, and I had so many eureka-moments reding it… I have made so many notes and references to things I want to remember. Just to showcase a little bit of what it holds, here are some subjects that it handles. See also the TED-talk by Kahneman below for an introduction to his two selves — the experiencing self, and the remembering self — and what impact it (should) have on our choices for the future.

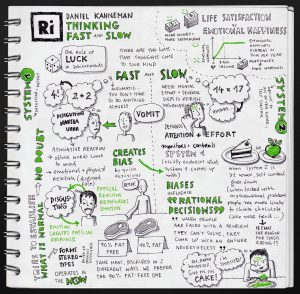

System 1 and System 2

Before presenting a few topics from the book, I have to introduce to you System 1 and System 2. To make it very brief here, one could characterize the two systems as

- System 1 – the fast one

-

- Responsible for automatic tasks, such as forming intuitions and emotions, reading facial expressions, retrieving trivial knowledge.

- Operates automatically and quickly. It is always running in your subconscious — cannot be turned off.

- Can be trained to execute pre-learned skills, such as automatic responses and experience-based intuitions.

- Responsible for storing, associating, and retrieving memories.

- System 2 – the slow one

-

- Deliberate thoughts and self-control.

- In use where mental effort is required. E.g. calculating difficult mathematical questions (what is 34 x 21?) or engaging in attention-requiring conversations.

- Can either endorse or reject information from System 1. Endorsed information manifests itself in beliefs, attitudes, and intentions.

- Is a scarce resource. You cannot play chess while calculating 34 x 21 while doing (non-routine) dancing while controlling your breath, etc. Actually, most often you can only do one task at the time requiring support from System 2.

- Is lazy. Often mistakes that we make arise from System 2 failing to catch non-well-founded impressions from System 1, jumping to false conclusions.

The details of these two systems are, of course, much much more complex — these are just to give you a brief sense of what we are talking about.

Sketch of “Thinking — Fast and slow” by Eva-Lotta Lamm.

WYSIATI

Not to be confused with WYSIWYG, the What You See Is All There Is is a concept that Kahneman introduces early on in the book and uses in so many contexts that it deserves its own acronym: WYSIATI. It basically means that when you evaluate a story, a set of facts, or impressions of people, etc., you only evaluate what is presented to you, and you often fail to counter in other facts that are not readily available to your System 1. Your System 2 fails to stop up and ask what is missing from the story. An example from the book1:

The measure of success for System 1 is the coherence of the story it manages to create. The amount and quality of the data on which the story is based are largely irrelevant. When information is scarce, which is a common occurrence, System 1 operates as a machine for jumping to conclusions. Consider the following: “Will Mindik be a good leader? She is intelligent and strong …”. An answer quickly came to your mind, and it was yes. You picked the best answer based on the very limited information available, but you jumped the gun. What if the next two adjectives were corrupt and cruel?

Take note of what you did not do as you briefly thought of Mindik as a leader: You did not start by asking, “What would I need to know before I formed an opinion about the quality of someones leadership?”

In short, after hearing the two first adjectives, System 1 immediately jumped to the conclusion that Mindik is a good leader, and even-though the two next adjectives may be negative, there will remain a bias favoring the first impression.

The premortem

One of the features of System 1 is overconfidence. Kahneman argues that it can be tamed but not vanquished, and that it arises from the fact that the validity of a story is based on it’s coherence — not by the quality or amount of data. WYSIATI. He draws out the premortem procedure, actually contributed by Gary Klein2:

The procedure is simple: when the organization has almost come to an important decision but has not formally committed itself, Klein proposes gathering for a brief session a group of individuals who are knowledgeable about the decision. The premise of the session is a short speech: “Imagine that we are a year into the future. We implemented the plan as it now exists. The outcome was a disaster. Please take 5 to 10 minutes to write a brief history of that disaster.”

I immediately found myself thinking of several scenarios where this exercise might have come in handy 😮

Anchors

Anchors are quite impressive as well — and can be (and most likely is) used in the advertisement industry. It is therefore a critical subject to know about in your daily life. I think I will just bring a small excerpt from the book, kicking off the subject3:

Amos and I once rigged a wheel of fortune. It was marked from 0 to 100, but we had it built so that it would stop only at 10 or 65. We recruited students of the University of Oregon as participants in our experiment. One of us would stand in front of a small group, spin the wheel, and ask them to write down the number on which the wheel stopped, which of course was either 10 or 65. We then asked them two questions:

Is the percentage of African nations among UN members larger or smaller than the number you just wrote?

What is your best guess of the percentage of African nations in the UN?

The spin of a wheel of fortune — even one that is not rigged — cannot possible yield useful information about anything, and the participants in our experiment should simply have ignored it. But they did not ignore it. The average estimates of those who saw 10 and 65 were 25% and 45%, respectively.

What is in effect here is the anchoring effect and seen from a logical standpoint it should not exist. Yet, it is one of the most reliable and robust effects documented in experimental psychology. An effect that you should be aware of, and (to some extend) can counter.

Other subjects

Other subjects in the book are

- the Law of small numbers

- the asymmetry between inferring the particular from the general and vice versa

- how bad impressions are more resistant

- over-estimating rare events

- story framing and moral effects

- death by pleasure

and more.

While reading it, I also came to think of a life lesson from my dad. I was in my teenage years and had just starting teaching badminton to kids younger than me. I remember, while preparing my teaching, my dad gave me this advice (recalled loosely from memory):

It does not matter how awful or uninspiring you session has been. Just make sure that the ending is good and fun, and your students will return.

While I (and probably not my dad himself) never thought it to be 100% true, it does hold a lot of truth in it, and it coincides with what Kahneman calls the duration neglect of memories. In short, you do not remember episodes by how long they are, but what the peak pleasure (or pain) was, combined with the end pleasure (or pain) of the event. He talks more about this and the notion of the two selves (the experiencing and remembering selves) here in his TED talk:

Final notes

If I have to say one negative thing about the book, it is that I found the later chapters in the book less founded and less intuitive correct than the rest of the book. In contrast to the rest of the book where I found myself either immediately convinced by his statements, or later, convinced by the following descriptions of his research, the later chapters presented points that I could not quite convince myself of was true. But perhaps I was just tired while reading those chapters, and I will definitely try to read the book again — if for nothing else, then just to absorb his good knowledge even more.

A final note is a reference to something I in my mind dubbed Death by Pleasure:4

Other classic studies showed that electrical stimulation of specific areas in the rat brain (and of corresponding areas in the human brain) produce a sensation of intense pleasure, so intense in some cases that rats who can stimulate their brain by pressing a lever will die of starvation without taking a break to feed themselves.

Has anybody else read the book Infinite Jest? If so, they know what reference I am making here…